Українська For the sake of viewer convenience, the content is shown below in the alternative language. You may click the link to switch the active language.

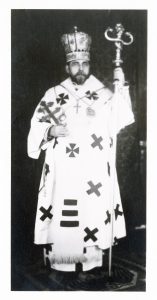

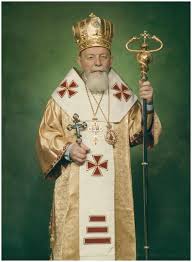

Rev. John Sianchuk, C.Ss.R.

Blessed Vasyl Velychkovsky, C.Ss.R.

– “Father of the underground Church in Ukraine”

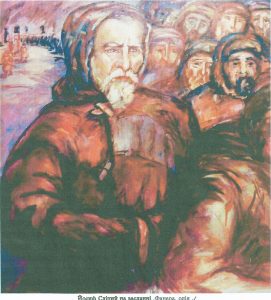

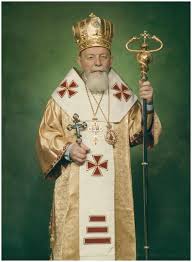

Over twenty years have passed since the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church has been able to practice its faith freely and openly. In 1946, this Church had been declared an illegal body by the Soviet Union. Its hierarchy arrested. Many thousands of clergy, religious and laity were imprisoned, tortured and even killed for their faith. In 2001, Pope John Paul II [1]during a pastoral visitation to Ukraine, took the opportunity to beatify a small number of these people and declare them to be Christian martyrs for the faith. Among those beatified was Blessed Bishop Vasyl Velychkovsky, a Redemptorist. This paper will describe Blessed Vasyl Velychkovsky’s activities during the underground Church in Ukraine from 1955 to 1969, both as a Redemptorist priest and later as a bishop. His leadership in these activities led Bishop Julian Voronowsky, who himself was ordained to the priesthood by Bishop Vasyl, to call him “The Father of the Underground Church.”[2] This paper will also include a brief presentation on his life, his two arrests, the interrogations and his imprisonment.

This paper is based on material found in the Blessed Vasyl Velychkovsky Shrine and Museum Archives, which are located in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. The sources used come from more than 70 interviews which were conducted since 2004 in Ukraine, taken with eye-witnesses who knew Bishop Vasyl personally and worked with him. These recorded interviews are limited by the clarity of memory of those being interviewed. However, much interesting information was uncovered. In 2009, documents from the first and second arrest were obtained from the SBU archives in Ukraine, (the former KGB archives). They comprise a total of six volumes with approximately 2000 pages. Material from Blessed Vasyl’s autobiography and other relevant documents were also consulted.

Vasyl Velychkovsky was born on June 1, 1903, into a priestly family in Stanislaviv (now Ivano-Frankivsk), Western Ukraine. His father Volodymyr was a priest, as were both his grandfathers, Julian Velychkovsky and Nicholas Theodorovych. Many of his uncles and aunts were in monastic orders or diocesan priests. Vasyl was mainly home schooled, spending some time in the Basilan juvenate of St. Josaphat in Buchach. During the First World War, he joined the Sichovy Striltsi, a Ukrainian rifleman regiment. He was captured, arrested, imprisoned, and then later escaped from prison. After returning home, he entered the major seminary in Lviv to study for the priesthood. During his diaconal year, in 1924, he joined the Redemptorist Congregation. This missionary congregation was recently invited from Belgium by Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky to work in Ukraine. A year later after his novitiate, he was ordained to the priesthood on October 9, 1925 in Zboisk, near Lviv. Most of his ministry was as a missionary preacher.

Soon after his ordination and after a brief period of being on staff in the Redemptorist juvenate in Zboisk, he was assigned to the monastery in Stanislaviv where he began giving parish missions. In 1928, he joined Father Nicholas Charnetsky[3] in the newly formed ministry in Volyn. Here he served immigrants from Halychyna. He also worked with the Orthodox faithful. Russian Orthodoxy was enforced in the Volyn region in 1885. Prior to this, the people of Volyn were mainly Greek Catholics. Fr. Vasyl was able to bring many of the congregations back to the Greek Catholic Church. He was always careful to maintain the Orthodox ritual. In Halychyna, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church was quite Latinized. Charnetsky and Velychkovsky were very careful not to introduce these elements into the church in Volyn. At that time, Volyn was part of Poland and the polish authorities, including the Polish church, had an agenda to polanize the Orthodox faithful. The Redemptorists, including Fr. Vasyl, refused to do this and in fact were doing the opposite by uniting these people with the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church under Metropolitan Andrey Shyptytsky. For this reason, under the pressure of the Polish government, Fr. Vasyl was forced to leave Volyn in 1935.

Fr. Vasyl returned to Stanislaviv and became the superior of the Redemptorist monastery. From there, together with other Redemptorists, he preached parish missions throughout parishes in the Stanislaviv region. The monastery chapel was an active centre of pastoral work. Being near the university, students frequented the chapel. Fr. Vasyl organized groups of young people. He had a ministry for young women coming from the villages, who were seeking employment in the city. These women would often fall into immoral situations. He organized them and gave them moral strength. They would later save him from early imprisonment. Not only students, but also the intelligentia would come to the monastery chapel for spiritual support from Fr. Velychkovsky, especially through the sacrament of confession.

In June 1940, while the Soviets had already occupied Western Ukraine for nine months, even against the advice of the local bishop, Hryhory Khomyshyn, Fr. Vasyl led a procession of some 20,000 people through the streets of Stanislaviv on the occasion of the feast of Our Mother of Perpetual Help. The Soviets were not confident enough to stop the procession. After a few days, Fr. Vasyl was called out for an interrogation. During this interrogation, he suffered both physically and emotionally. After a day, the police released him, fearing the growing protests of the young women who were ready to lay down their lives for their spiritual father.

During the Nazi rule over Western Ukraine, 1941- 44, Fr. Vasyl spent most of his time in priestly ministry in Ternopil. He was in Lviv, when the Soviets were advancing upon the city in 1944. Because of the extreme danger, his religious superiors advised him not to return to Ternopil. However, he embraced this precarious situation and journeyed back to look after the people in that city – the sick, the orphans and the elderly, who could not leave or escape the advancing Soviet army.

As the war was ending, on the night of April 10-11, 1945, the Soviets arrested many of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Bishops, including Metropolitan Josyf Slipyj, Bishops Nicholas Charnetsky, Nykyta Budka, Hryhori Khomyshyn, and Ivan Latyshevsky. Many clergy were also arrested. On July 26, 1945, the order to arrest Fr. Vasyl was given. Because he kept giving short missions in various villages, the authorities could not find him. However, on August 7, 1945, he was at the monastery in Ternopil when the NKVD came, did a house search, and arrested him. In the police station, he was given the choice to join the Russian Orthodox Church and be released or refuse and be incarcerated, perhaps even face death. Fr. Vasyl refused to sign any documents. With an authoritative voice, he replied: “No, Never! Under any circumstances… I have said NO once and for all; and you can shoot me, and kill me, but you shall get from me no other word.” [4] He was taken to the basement of the NKVD headquarters in Chortkiv for two months. During this time no investigation concerning his case was done. However, during this time in order to influence him to join the Russian Orthodox Church, he was physically tortured.

He was later transferred to Kyiv to the Lukianivska prison. Here the formal investigation of his criminal case began. The purpose of this investigation was not to search for evidence nor conduct interviews with witnesses who could prove his criminal activity, but to torture him until he confessed to crimes he never committed. He was interrogated eleven times, some lasted twelve hours, one lasted two days. Usually, the interrogations were conducted at night. Sleeplessness, isolation, food deprivation, physical and moral abuse helped to breakdown his will-power. Finally, he confessed to the crimes of which he was being accused. Eventually, Fr. Vasyl “confessed” to having published a small calendar in Stanslaviv, which contained the words “save us from the red horde”. [5] This was enough to trump up a charge of anti-soviet propaganda. Only then on January 8, 1946, did they formally charge him with a crime. He was formally accused of conducting anti-Soviet propaganda by: preaching sermons with an anti-Soviet context; organizing anti-Soviet organizations; supporting the anti-Soviet activities of the Ukrainian nationalists by writing a greeting in a nationalist newspaper; organizing an anti-Soviet celebration in honour of the German occupants; and publishing anti-Soviet nationalist literature.[6] The investigator had proof for all the charges listed above and most importantly the accused agreed to the accusations presented to him. His trial was held on June 26, 1946. He was quickly found guilty. Therefore, “taking to account the status of the accused and the level of his criminal actions […] the Regional Court sentences Velychkovsky […] on the basis of article 54-10 of USSR to the highest level of retribution by firing squad with the confiscation of all his possessions.”[7] His trial was conducted improperly, since he only saw his lawyer for the first time in the courtroom. His sentence was based on the unjustly conducted investigation and on his forced confession. Even though the whole case was conducted so unfairly, Fr. Vasyl receives the highest form of punishment, that is, to be executed by a firing squad.

He spent approximately three months on death row. Notwithstanding that he was condemned because he would not abandon his Catholic faith, he continued his priestly ministry in prison. In some sense, this is where Fr. Vasyl’s underground church ministry began. At the request of his fellow-prisoners on death row, he began to catechize them and prepare them for death.[8] Sr. Innocentia Sytko, who worked with Fr. Vasyl in the underground church, shared that he gave the prisoners a ten day retreat during which time no one was called out to the “wall.”[9] After three months when his name was called, he left his cell ready to give up his life for his beliefs. However, his sentence was changed to ten years of hard labor in the Soviet laager camps. He first spent a year and a half in camps near Kirov working in the forest. Then he was transferred to work in the coal mines in Vorkuta, which is north of the Arctic Circle.

From a fellow prisoner in Vorkuta, Boris Mirus, it is known that Fr. Vasyl continued his pastoral work in the laager camps. Fr. Vasyl confessed the prisoners, counseled and consoled them. “He had a colossal faith in God, in the Church, in Christ, and when I remember him, I think ‘This man can endure all sufferings like Christ on the Cross.’ He confessed us, although that was forbidden and very dangerous if caught. But he confessed in the mine shafts…During confession, he was very dignified. After we all felt better and lighter. Many of the men went to him… all came to him and confessed especially on the feast days.” [10] He would daily celebrate the Divine Liturgy early in the morning in the barracks on his bed, using a large tablespoon as his chalice. The wine he used was made from raisins, which he occasionally received in packages from home. He also celebrated the Divine Liturgy on feast days deep in the mine shafts. Mirus described being present at these Liturgies and how those trusted, would all gather around 4 am in a dark mine shaft, placing two guards on either side of the shaft in case of any intruders. Then silently and profoundly, Fr. Vasyl would celebrate the Holy Mysteries and offer communion to those present. These services made a deep impression on Mirus. “We would gather in the shafts for the Service. I was present when some fifteen to twenty men, who were believers, honest people, would gather with guards on either side.”[11] He also shared how Fr. Vasyl was always praying on a home-made rosary, made of prison black bread and string. He prayed for the prisoners and for the guards. These difficult circumstances formed Fr. Vasyl for the work he would later do in the underground church.

Fr. Vasyl had a great authority in the camp. Even the guards feared and ‘respected’ him. On the important Soviet commemorate days (May 1, etc.), he was thrown into solitary confinement so that he would not be able to start any protests. “They considered such a man dangerous during their feast days, that he would begin some agitation or protests, for he knew how to organize people… therefore, two or three days before these feast days, they threw him into an interior prison.”[12] After Stalin’s death in 1953, many riots broke out in the laager camps. Fr. Vasyl was falsely accused of initiating the one that occurred in his camp. He was then transferred to the infamous severe prison in Vladimir near Moscow. In 1954, Fr. Vasyl was sent back to Vorkuta, because of a protest letter[13] he wrote to the General Procurator of the Supreme Soviet in Moscow in which he claimed his innocence. On July 9, 1955, he was released from prison and sent to Lviv. He found an apartment in the inner city of Lviv, 11/3 Soborna square. He shared this apartment with a Redemptorist brother, Brother Irenee Manko.

Fr. Vasyl arrived in Lviv to find all the Ukrainian Greek Catholic churches closed. All religious monasteries were disbanded. On March 10, 1946 during the so-called pseudo- Synod of Lviv, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church was declared an illegal body. Officially, its members joined the Russian Orthodox Church. It now became illegal to openly practice the Ukrainian Greek Catholic faith. One could not gather for any services. The priests could not celebrate public Liturgies, conduct baptisms, marriages or funerals. Catechism could not be taught. Neither retreats nor missions could be preached. Seminarians could not be formed and educated. Religious life was illegal. One could not organize monasteries. Even listening to foreign religious programs was forbidden. Anyone caught doing any of these religious acts could be arrested and imprisoned. No longer did the Soviets have to prove anti-soviet propaganda to arrest a person. To incarcerate someone, it would be enough to prove that they were involved in Ukrainian Greek Catholic activity.

Thousands of priests, religious and faithful had been arrested for their religious activities or their association with the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. Those who remained and those who had returned from imprisonment were afraid to do anything religious for fear of being arrested. When Fr. Vasyl returned from his imprisonment, according to Bishop Julian, “he was a very energetic man. He was energetic and was able to inspire others. Even though he was not the bishop, he gathered all priests to his place and organized them for their religious work.”[14] Fr. Vasyl’s own apartment became the center of religious activity. This was even more evident after he was consecrated a bishop. His apartment was established as his chancery and cathedral. Fr. Vasyl began to organize a secret church. He designated trusted homes in which the sacraments, especially the Eucharist could be celebrated. Often they would gather in the evenings, late nights and early mornings in private homes to celebrate the Divine Liturgy, conduct baptisms and marriages.

The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church is very rich in rituals, music, religious art, icons, vestments, religious space, including the iconostasis. It has many prescripts regarding the religious services – where to stand, who does what part, how to sing, what ritual needed to be performed. On the surface all of these seemed to be taken away by the Soviets and forbidden. However, the experience of the prisons taught priests, like Fr. Vasyl, what is essential in celebrating the Holy Mysteries.

Under these extraordinary circumstances, ordinary tables now became altars. Vestments were minimal. Perhaps an epithrahil, (the priest’s stole), was the only vestment. A small wine glass made of glass or metal was used for the chalice, and a teacup saucer for a discos. The objects used for the Divine Liturgy, including the altar linens, chalice coverings and any vestments, were all kept separately in secret compartments and used only for this purpose. Even after 30 years, religious sisters and laity, in whose homes these Liturgies were celebrated, kept these objects in a special reserved place. The vessels were often hidden under floor boards, behind the ceramics of an oven (peech), or in a dresser or china cabinet. During a police search of the house, most of the objects, except for vestments, could be passed off as objects for ordinary use and not religious objects. These searches were done regularly and continued until the late 1980’s.

Fr. Vasyl’s own apartment was also converted into a chapel. A cabinet became his altar and an ordinary wooden ‘jewelry’ box his tabernacle for the Holy Eucharist. A plastic flowered lamp served as an “eternal flame”. On the altar were the altar linens. The liturgical books (if any, since many were confiscated) and sacred vessels, which were always in a diminutive size, were kept in the drawer of the cabinet, or hidden under floor boards. Over the altar was an image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and the Icon of our Mother of Perpetual Help. This latter icon was particularly precious because it had hung in the Redemptorist Minor Seminary in Zboisk. During the Second World War, a soldier shot at it with his revolver several times piercing it. This icon symbolized that the Mother of God also suffered with her people. The altar area was covered by a curtain to emphasize the sacred space and that it would not be quickly seen by an unwelcome visitor.

Organizing a Divine Liturgy in people’s homes was also very dangerous. These Liturgies were usually celebrated late at night. They had to be secretive. Only those people who were trusted were invited. Children, in particular, were often not told for fear that they would tell someone else. If the home did not have the sacred vessels, then Fr. Vasyl would have someone else, often a religious sister, carry the package. If she was caught, then she would plead ignorance as to the contents of the package. Sister Modesta Senyk described being caught one day as she carried the chalice, books and vestments for Fr. Vasyl.[15] Someone had come to the home when the Liturgy was being celebrated unannounced. This person left early. They suspected that this person had told the authorities about the service. By the time the authorities arrived, the service was over and people, including Fr. Vasyl had escaped. However, Sr. Modesta, who was carrying the package, was caught and interrogated all night. She was able to deflect all the questions so that neither Fr. Vasyl nor she nor the people of the house in which the Liturgy was celebrated were arrested.

Fr. Vasyl, being a Redemptorist, desired to give missions or at least retreats. Missions would be impossible to give since they were so public, but retreats could easily be given in homes. His first retreat was given to a group of women in Lviv in August 1955 in Julia Tverdohlib’s apartment. She gathered a number of women and they had a “weekend” retreat – Friday evening, Saturday and Sunday. Some of these women would become the future vocations for various monastic orders in the underground church. This would be the first of many such retreats, given to laity, sisters and priests. The retreat conferences became a major way through which he formed the church, establishing and deepening the faith within this atheistic, hostile environment.

Fr. Vasyl was responsible for the renewal of some of the religious orders in the underground church. The religious monasteries for sisters had all been confiscated and closed in the late 1940’s. Individual sisters were scattered throughout the city. Fr. Vasyl was particularly close to the Basilian Sisters. His aunt, Sister Monica Polanska, [16] his mother’s sister, had been the superior of the Basilians before the Soviet liquidation of the institution. Fr. Vasyl sought out the sisters that were in Lviv and its surrounding villages, Rudno, Zymna Voda and others. He began holding regular retreats and days of renewal for these sisters. He invited young girls to come and join them. “He started to centralize our sisters. He began to accept new vocations… Before the sisters were scattered and lived the monastic rule as they could. He gathered us together.” [17]

Throughout the years, Fr. Vasyl purchased ten homes for the Basilian sisters in Lviv, Zymna Voda, Rudno, Ternopil and other places.[18] Two to four sisters would live in these homes. Often the sisters had secular work. While at home, they lived a strict monastic routine. However, not all were able to live in these homes so they kept the monastic rule as well as they could in their own homes. They would gather in one of the homes for retreats and days of renewal given by Fr. Vasyl. He gave these retreats every two weeks or at least once a month. While confessing a young girl, if Fr. Vasyl felt that she had a vocation to the monastic life, he would invite her to come to one of these retreats. At the end of the weekend retreat, the young candidate would make her first commitment and begin to live the monastic life, first at home and later as circumstances allowed, she would come to live in one of these homes. Sister Iryna Korduba from Ternopil, a medical nurse, was assigned to keep a record of those who joined the Basilian Order. Fr. Vasyl brought 103 sisters into the underground Basilian Sisters Order.[19] In this way the religious order not only survived the time of religious persecution of the Soviets, but even grew and flourished.

The spirit of these sisters was filled with great fervor and courage. They were women of great faith and prayer. Sister Claudia Velhosh, related that on one occasion while a retreat was happening in one of these homes in Zymna Voda, one of the sisters saw the police coming down the street. The home was filled with sisters and candidates. The new habits were laid out for those who were joining the Order that day. Fr. Vasyl was with them and asked them to pray for protection. One of the sisters grabbed a bowl of chicken feed and ran outside to feed the chickens. She and the chickens were making a great racket. As the police arrived at the gate, the sister’s fast talk and energetic movements caught the police off guard. She told them that she was alone in the yard and house. If they came any closer, she would cry out to the neighbors. The police became confused and left. The sister returned to the house and the religious ceremony continued. [20]

Another incident Sr. Iryna Korduba related, reveals the level of faith and prayer that existed in this underground Christian community. One Christmas Eve in 1958, in Ternopil, Fr. Vasyl came to spend Christmas Eve with the sisters and his mother Anna, (Sr. Emilia), who entered the Basilian Order through Fr. Vasyl’s assistance in 1956. Approximately 12 people, consisting of sisters and laity, were in the house/monastery for Christmas Eve supper. After the meal, as they waited for midnight in order to begin the Christmas Divine Liturgy, the KGB came to the door. Those inside feared their immanent arrest and began to hide. The KGB knocked insistently, but the sisters refused to open the door. Instead the door was barred and the lights were turned off. The police continued knocking, shouting threats and waiting. Inside, Fr. Vasyl had ordered all those present to pray intensely. This stand-off lasted several hours. Finally, Fr. Vasyl took the cross that he was holding, came to the door, said a prayer for protection, and made the sign of the cross over the door. Immediately, the KGB left. After making sure they were gone, the Christmas Midnight Liturgy was celebrated and after the Liturgy all those inside went to their respective homes. [21] Moments of such persecutions were common for the sisters and Fr. Vasyl.

During the first few years in Lviv, after returning from Vorkuta, Fr. Vasyl had the assistance of Bishop Nicholas Charnetsky, a fellow Redemptorist. In 1956, Bishop Nicholas returned to Lviv after eleven years of imprisonment. His health was ruined. He lived on 7 Verchirnya Street in Lviv, where he spent most of his days in prayer. He was the senior bishop and acting head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in Ukraine. The head of the church, Metropolitan Josyf Slipyj, was still in prison. However, according to Bishop Julian Voronowsky, Bishop Charnetsky was not instrumental in organizing the secret pastoral activity of the church. He did ordain some priests, but he was afraid that if the police questioned him, he would not be able to hide this fact. When asked to ordain Velychkovsky to the episcopacy in 1959, he was frightened and unable to do so. He relied on God to provide someone to ordain him.[22] In fact, it was Fr. Vasyl to whom the priests and sisters came for direction. Fr. Vasyl, in turn, himself would frequently visit Bishop Nicholas for advice and counsel. They had lived and worked together in Volyn for seven years and were very close.

After Bishop Charnetsky’s death, [23] Fr. Vasyl’s role of leadership became even more pronounced. Some of the young Basilian Sisters, among whom were Sr. Justyna (Julia) Trevdohilb, Sr. Anna Shewchuk, Sr. Anhelina Chayka, Sr. Innocentia Sytko, and others, became his close co-workers. Sr. Anna who was his cook, became his close confidant and helped him in organizing the ministry. Sr. Innocentia became his secretary, coming daily to his apartment. They were his messengers; bringing news to Fr. Vasyl concerning the need for baptisms, funerals, and Liturgies. He, in turn, would assign priests to fulfill these works. Sr. Anhelina was very small in stature and could easily be lost in a crowd. The police would have a hard time following her. Because of her ability to elude the police, she was often assigned to take messages, vestments, holy cards, church utensils to people’s homes. Sr. Justyna lived only ten minutes away from Fr. Vasyl’s apartment and would visit him often. She was a seamstress and sewed many of the vestments used by Fr. Vasyl and other priests. Later, she also made antimensions[24] for him after he became a bishop. She kept in her apartment many holy pictures, which Fr. Vasyl produced.

These holy cards could not be reproduced by ordinary means. Vasyl Manko, the brother of Bro. Irenee, was a photographer and had a darkroom. He would photograph holy cards and then reproduce them on photo paper. The process was slow but effective. Similar methods were used to reproduce small prayer booklets, such as “The Way of the Cross”. The pictures were then bound together into a rather thick booklet. The reproduction of such objects was illegal in the eyes of the government and could be the cause for arrest. Fr. Vasyl had made many such booklets. When the police raided Sr. Justyna’s apartment in 1963, they confiscated many these religious objects. She was arrested and received a six month sentence. Throughout the interrogations, she was able to remain faithful and not name Fr. Vasyl as the source of these religious items.

Even before becoming a Bishop, Fr. Vasyl began to accept the “apostate” priests. “When Velychkovsky came, he agreed to accept those former catholic priests who signed with the Russian Orthodox Church. They first had to confess the symbol of faith and to receive a penance for their action.[25]

Some were asked to remain in the parish where they were already celebrating, with the stipulation that they would not concelebrate with “non-united” priests.” [26] Fr. Vasyl was also responsible for having men ordained to the priesthood. He vouched for their readiness for ordination, inviting Bishop Ivan Sleziuk[27] from Ivano-Frankivsk to ordain them. Unfortunately, Bishop Sleziuk was arrested in 1962. This left an episcopal vacuum in the underground church.

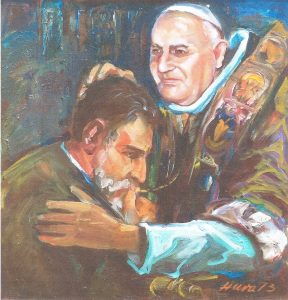

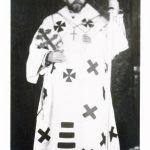

There were a few underground secret bishops, but they were either in prison or in exile. The Vatican did an investigation to search for a worthy candidate for the episcopacy and appointed Fr. Vasyl Velychkovsky in 1959.[28] Unfortunately, there were no bishops available in Ukraine who could consecrate him to the episcopacy. In October, 1962, Pope John XXIII called together all the Catholic bishops of the world for the Second Vatican Council. The Vatican was aware that Metropolitan Josyf Slipyj, the head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, was at that time imprisoned in Soviet laager camps. Pope John XXIII petitioned the Soviet Union to have Metropolitan Josyf released to enable him to attend the Council. President John Kennedy also added his voice to this petition. With all this pressure, the Soviets negotiated the release of Metropolitan Josyf. While he is in Moscow awaiting for an emissary to arrive from the Vatican to escort him to Rome, he wrote a letter[29] to Lviv, asking Fr. Vasyl to come immediately to Hotel Moskva, room 624, because he has need of him. Upon receiving this news, Fr. Vasyl told his cook, Sister Mykolaya,[30] that he had to go to Moscow. When he arrived at the hotel, Metropolitan Josyf was already making his final plans for his trip to Rome. When he saw Fr. Vasyl at the door, Metropolitan Josyf asked those in the room to leave, because he wanted to be with his ‘family’ alone. As soon as everyone left, Metropolitan Josyf asked Fr. Vasyl to kneel down and the rite of Episcopal consecration began. The details of this event were related by Bishop Vasyl to Father Michael Hrynchyshyn, [31] the Provincial of the Redemptorists in Canada, and to a Redemptorist confrere, Fr. Joseph Denischuk. Even before the abbreviated ritual was concluded, the authorities were already knocking at the door to take Metropolitan Josyf to the train station for his trip to Rome. The ordination rite was concluded. Metropolitan passed on his wooden walking stick, symbolizing the Episcopal staff, to Bishop Vasyl. In this way he passed on the authority to Bishop Vasyl to govern the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in Ukraine, making him the “acting head” of the Church. The door opened and Metropolitan Josyf was taken away. The newly consecrated bishop returned to Lviv with this new responsibility of governing this catacomb church. This event took place February 4, 1963.

His Episcopal consecration was kept a secret. Only a chosen few knew about it. Bishop Vasyl returned to his apartment in Lviv, which now became his chancery and his cathedral. Daily he received priests daily in his apartment, coordinating the various ministries – baptisms, marriages, Divine Liturgies, funerals and the like. Often there would be four or five priests at a time in his apartment/chancery. They were treated first to a meal if necessary. Fr. Ivan Dankiw, C.Ss.R. shared that the first question asked always was: “Have you eaten today?”[32] It was a close-knit and very personal system. It was impossible to have any general meetings of clergy – “soborchyky”. The only way to govern the church was personally with those trustworthy.

He continued his work with the sisters, especially the Basilian Order, but also with the Sisters of Mercy of St. Vincent de Paul, the Sister Servants of Mary Immaculate and the Sisters of St. Joseph. He also organized a group of laity, calling them the “Third Order”. This “Order” gathered regularly for prayer and were often the eyes and ears of the church with regards to the activities of the police and the needs of the faithful. This group, started by Bishop Vasyl, continued under the spiritual chaplaincy of Fr. Myhaylo Vynytsky,[33] and remained a force of evangelization in the church until its freedom in 1991.

Secret seminaries were organized in Lviv and Ternopil. The students were tutored by other priests, often one by one or in a small group of two or three. Since it was impossible to obtain any text books for philosophy and theology, the seminarians would copy by hand entire books. This was very time consuming and thus these hand written books became very precious. Because of the danger of possible house searches, these text books were hidden in plastic bags and buried in gardens. A freshly dug patch in a garden would not be suspected by the police. Often the seminarians did not know each other. Their identity was kept secret so that they would escape being arrested. Their classes were conducted in the evenings or on days when they were free from their jobs. Each seminarian and priest was required to have some employment. The seminarians were secretly ordained in ordinary homes. Even family members rarely knew about it or attended the ordination. The bishop alone was aware of all the priests and who it was who could assist him in any particular ministry. It is unknown how many priests were ordained by Bishop Vasyl. Priests were essential for the sacramental life of the church. As Bishop Voronowsky stated in his interview: “When Fr. Vasyl became a bishop, then he himself began to ordain priests. Even in our house, he ordained our Father Archmandrite Nykaphor Denegato to the episcopacy in 1968.”[34]

Although the danger of being a priest was great, yet at the same time the faith was very alive, lived with joy and hope. Sr. Muza Solomon described one such day in the life of Fr. Vasyl. Sr. Muza, a Basilian sister, was a close co-worker with Bishop Vasyl. It was arranged that three Lithuanian [35] seminarians were to come to Lviv to her house, where Bishop Vasyl would ordain them to the priesthood. In the afternoon, Bishop Vasyl sent a message to Sister Muza that he would be late, because the police had summoned him that day to come for an interrogation. He asked her to tell the men to wait. The interrogation took several hours in which the police questioned him about his activities as a priest. Bishop Vasyl was able to deflect all their questions and revealed nothing about the state of the church. After this was completed, he gave a spiritual conference to sisters in another home. Only then did Bishop Vasyl arrive at Sr. Muza’s about 10:30 in the evening. She relates that in candle light and in a hushed voice, the bishop celebrated the Divine Liturgy and ordained the three Lithuanians. They had to do this quietly and by candlelight because a KGB officer lived next door. She recalled, with tears in her eyes, the Christian joy she experienced in these austere circumstances – no choirs, no elaborate rituals or vestments, no cathedrals filled with icons – but a profound sense of the presence of God and of His grace. [36]

In order to ensure that the catacomb church continue, if and when he would be arrested, Bishop Vasyl Velychkovsky consecrated a fellow Redemptorist priest, Fr. Volodymyr Sterniuk, to the episcopacy on July 2, 1964. Bishop Volodymyr’s identity was kept secret and he was not to function as a bishop. He would only do so, if Bishop Vasyl was arrested or exiled. Bishop Volodymyr was ordained with the right of succession. This in fact took place when Bishop Vasyl was exiled from Ukraine in 1972 after his second arrest and imprisonment. Bishop Volodymyr led the catacomb church from the underground into a legalized church after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.

The consecration of Bishop Volodymyr was perhaps the most important act of Bishop Vasyl’s legacy. This historical event ensured that the underground church would survive this time of persecution. Bishop Julian stated: “In my opinion, Bishop Vasyl’s great contribution to the church was his ability to provide for the future of the church.”[37] At the time of Bishop Vasyl’s consecration and subsequently Bishop Volodymyr’s consecration there were no other bishops in Ukraine. Those who were still living were in prison or exile.[38]

In 1966, under Khrushchev’s new policies, religious persecution seemed to be more relaxed and some believed in the possibility of the legalization of the Church. This prompted Bishop Vasyl to take a course of action attempting to bring some freedom for the Church. At the same time in his protest to Moscow, he took this opportunity to defend himself for his unlawful arrest and incarceration. Sr. Onufria Maik, a Sister Servant whose brother was a Redemptorist, heard from her brother that “Bishop Vasyl gathered signatures from Ukrainian Catholics and personally went to Moscow to deliver this petition. He travelled to the government ministry … requesting that they return at least one church to the Ukrainian Catholics in Lviv.” [39] Vasyl Manko also shared details of this trip to Moscow. “Bishop Vasyl arrived in Moscow and went to the General Procurator … dressed in a military overcoat… with a walking stick in his hands… When he approached the offices, instead of being stopped and questioned, the guards saluted him and opened the doors for him. The same happened all the way until he found himself surprisingly before the head of the department.”[40] However, his petition for relaxed norms for the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church fell on deaf ears.

In the spring of 1967, Bishop Vasyl was given permission by the government to travel to Zagreb, Yugoslavia to visit his sister Vera Nikolic, who was ill. He was there from April 15 to May 8, during which time he wrote an autobiography[41]. Knowning that Bishop Vasyl was in Zagreb, Cardinal[42] Josyf asked Metropolitan Maxim Hermaniuk together with Archbishop Gabriel Bukatko and Bishop Joachim Segedi to go to Zagreb and conditionally consecrate Bishop Vasyl. It is said that Cardinal Josyf wanted to make sure that there was proper succession, in case there was any doubt about his secret consecration in a Moscow hotel room. Secretly Metropolitan Hermaniuk traveled with a Basilian priest and some sisters to Zagreb. The conditional consecration took place in the seminary chapel on May 3, 1967. [43] When Bishop Vasyl returned to Ukraine, he shared with Bishop Volodymyr Sterniuk that his consecration had been conditionally fulfilled. Bishop Sterniuk immediately knelt down and asked for the same conditional fulfillment.[44]

Bishop Vasyl’s brief stay in Zagreb opened the opportunity to share letters and news about the underground church and to receive communication from Rome. Bishop Vasyl wrote to the Redemptorist Superior General detailing the state of the Redemptorists and the Church. The Redemptorists in Ukraine had thirty-four priests, thirteen brothers, seven novices, two bishops and seven homes.[45] Following his meeting with Bishop Vasyl, Metropolitan Maxim wrote to the Vatican regarding the state of the church.[46] Bishop Vasyl also received a letter from the Basilian Protoarchmandrite, Atanasij Velykyj, in Rome, clarifying the position and authority of the Basilian fathers in Ukraine.[47] The situation between the Basilian fathers in Ukraine and Bishop Vasyl at times was tense. This letter attempted to clarify any misunderstandings.

Shortly after returning to Ukraine, Bishop Vasyl received two more documents. Both of them came from Cardinal Josyf Slipyj. They were written in point form in response to questions posed by Bishop Vasyl. One of the documents[48] was signed with a secret mark, a monogram, identified by Bishop Hrynchyshyn as belonging to Cardinal Josyf. The other document[49] was typed on a piece of cloth with no signature. From its contents, it is evident that it came from Cardinal Josyf. As the original letters from Bishop Vasyl have not yet been found, one can only guess what questions are being answered.

The document written on paper gave general directives and policies of church discipline: questions concerning validity of marriages; taking of promises before communists; membership in communist organizations; benefit of listening to Vatican Radio; usage of the word “orthodox” in the Liturgy; appointments of superiors of monasteries; obtaining and keeping lists; and questions concerning stipends. The Church needed direction in the new circumstances it found itself. There were no marriage tribunals, nor any desire to keep records which could be confiscated and used by the police to make arrests. The document typed on cloth is much more personal and directed to Bishop Vasyl, giving him guidelines how to conduct himself as a bishop. The statements were filled with caution: about making any statements; believing any gossip; whom he should receive in audience; whom he should ordain; and even to be aware of certain priests who could be spies. [50]

Bishop Vasyl, as the head of the underground Church, did hold meetings to help organize the activities of the church. Orest Vynytsky, whose brother was Fr. Myhaylo, a Redemptorist priest, shared with us that a meeting of church leaders took place in his house in 1967, after Bishop Vasyl’s trip to Zagreb. Vynytsky was asked if he would “allow several priests to come and have a meeting in [his] house? … Many priests came, older ones… many Basilians… when Bishop Velychkovsky arrived they all went up to the second floor to a meeting room.” [51] He did not recognize all those attending, but he knew that it was a highly secret and important meeting. The meeting was arranged by and called by Bishop Velychkovsky. Among those present were: Father Peter Horodetsky, Bishop Josaphat Fedoryk, Basilian priests and many others – approximately eleven people. The meeting was secret, therefore, there is little information about it.

Vynytsky overheard a heated discussion about some documents and concerning the use of the word “orthodox”. One of the burning topics of the day in Ukraine centered around the use of the word “orthodox” in prayers, in particular, the prayer of the Great Entrance of the Divine Liturgy. There were those who refused to use this word, because the Russian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate was the one persecuting Ukrainian Catholics and had confiscated many of their churches. Others, along with Bishop Vasyl, insisted that the word be used because: it corresponded to the ancient usage of the word in the Liturgy; it reflected the spirit of Vatican II; and most importantly, that it was the wish of the Cardinal Josyf Slipyj. Bishop Vasyl had the documents from Cardinal Slipyj to support his arguments.

Even though it was illegal to print or publish religious material, Bishop Vasyl courageously wrote a book to inspire and encourage the faith of the people. I966 marked a hundred years since the ancient icon of Our Mother of Perpetual Help was given to the Redemptorist Congregation. The Vatican asked them to spread her devotion throughout the world. Since then, this icon has become one of the most known icons throughout the catholic world. Bishop Vasyl, in thanksgiving to the Mother of God for her protection, wrote a book “The History of the Miraculous Icon of our Mother of God of Perpetual Help.”[52] This was a spiritual reading book on the history of the icon interspersed with inspiring stories. This book was hand written by Bishop Vasyl, then typed using carbon paper. In this manner, copies were made and then bound into books. This book became one of the main reasons for his second arrest as it was illegal to print religious books. Also within this book there were some examples of Soviet persecutions.

In 1968, a new wave of persecutions began. The anniversary of Lenin’s 100th birthday in 1970 was approaching and the Soviet government was frustrated that the Uniate Church (Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church) still existed in a catacomb manner. Bishop Vasyl feared imminent arrest, so he consecrated more bishops: Petro Kozak, Ivan Chorniak, Josyf Hirniak, and Nykanor Denega.[53] They were to remain secret and not function unless absolutely necessary, that is, if and when those functioning were arrested.

Many priests were interrogated and arrested. The KGB did a search of Bishop Vasyl’s apartment on October 6, 1968. “The police destroyed the prayer room, and confiscated religious books and church vestments.” [54] They returned again in January and again ransacked his room to find evidence for his arrest. On January 27, 1969, according to Fr. Bohdan Smuk[55], “The bishop was arrested. He was caught in Olha’s house where he kept his episcopal vestments and regalia.”[56] Sr. Muza happened to walk into her co-worker Olha’s home the moment of his arrest. She said: “I came to visit her. Strangers opened the doors for me. I wondered what was happening. Then, I realized that it was a house search…. I had come to pass on to Bishop Vasyl a letter requesting baptisms and a marriage. We just looked at each other. As he was being taken from the room, with his hands cuffed behind his back, he blessed me for the last time.”[57]

He was taken to a prison in Lviv on Horodetska Street. He remained in prison for eight months before his trial. During these eight months, he was interrogated numerous times in order to make a solid case against him. Many other ‘witnesses’ were also interrogated in order to prove his guilt. Even children were brought in to say that they received the sacraments from Bishop Vasyl.[58] While in prison, his health was very poor and in fact, at one point, he was declared clinically dead. This news spread to the “free world”. However, as the guards were taking him to the morgue, they felt some warmth under his armpits. They let him lie on the table and to their surprise, he regained consciousness and got up. “He was pronounced clinically dead …It was announced throughout Lviv that he had died, but later he revived and the police confirmed that he was alive.”[59]

His trial took place in Lviv on September 23, 1969. The general accusation from the court was “since he was an adherent of the Greek Catholic (Uniate) Church, he systematically and knowingly spread verbally and in written form false information about the Soviet communist government.” [60] The particular accusations were the following: writing a religious book “The History of the Miraculous Icon of our Mother of Perpetual Help”; listening to religious programs on Vatican radio; organizing and supervising theological courses in Ternopil for the formation of future priests; catechizing a minor in the teachings of the faith; reproducing and disseminating religious pictures and antimensions; and being accused of posing as a bishop.[61]

He was sentenced under the “Article 187-1 CC USSR … and by Article 138-2 CC USSR to three years of incarceration…. in a hard-labor correctional institution of strict regime.”[62] This sentence was served in Komunarsk, in the Luhansk region. This prison was a hospital for the psychologically ill. Sr. Anna Shewchuk and Vera Nikolic made appeals for Bishop Vasyl’s release, but to no avail. He was quite ill in prison. His feet became so swollen that he was unable to walk. Just as he was giving up all hope, a new doctor arrived who had mercy on him and admitted him for treatment. He received visits from Sr. Anna, on a regular basis every few months. From her visits, she saw his physical and mental deterioration. After he completed his three year sentence, he was released to Kyiv on January 27, 1972. Sr. Anna and Sr. Justyna visited him is Kyiv. Sr. Justyna described the meeting: “We went [to Kyiv]. Anna [Shewchuk] prepared some things to pass on to him. She took some clothing.… When I looked at him, he wasn’t a person but only a skeleton. I was so disturbed that I could not talk. We spoke a bit. He said that they tortured him very much for the book he wrote.”[63]

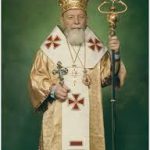

Bishop Vasyl was exiled from Ukraine. He was sent to visit his sister Vera in Zagreb, but realized that he had no return documents. After two weeks in Zagreb, on February 22, 1972, he arrived in Rome. He visited with Cardinal Josyf Slipyj and had an audience with Pope Paul VI. Metropolitan Maxim Hermaniuk, a Redemptorist archbishop from Canada, invited him to come to Winnipeg. Bishop Vasyl also had a first cousin, Maria Matwychuk, who lived in Winnipeg. He arrived on June 15, 1972. While in Canada, he visited all the Canadian eparchies, giving the annual priests’ retreats. He also travelled to Newark, Philadelphia and other centers in the United States. His health began to fail him.

While in Canada, the amount of damage and destruction that was done to Bishop Vasyl in prison became evident. Bishop Michael Wiwchar, who lived with Bishop Vasyl for a time, witnessed that during his last imprisonment, he was tortured by the administration of harmful chemicals. These chemicals caused heart disease and the destruction of the nervous system. He was also tortured by the use of electricity.[64] Maria Matwychuk shared the same information in an interview. [65] Doctors in Winnipeg, who cared for Bishop Vasyl were shocked at the evidence of torture on his body. On June 30, 1973, Bishop Vasyl succumbed to his tortures. He was buried in a Catholic Cemetery of All Saints near Winnipeg.

He was beatified on June 27, 2001 in Lviv by Pope John Paul II. A year later, September 22, 2002, his holy body was transferred from the cemetery to a Shrine built in St. Joseph’s Ukrainian Catholic Church. Upon exhumation, it was found that his body remained as it had been buried- fully intact. The Blessed Vasyl Velychkovsky Shrine has since become a place of pilgrimage for thousands. The Museum and Archives contain many of his precious artifacts and documents.

The importance of Blessed Vasyl Velychkovsky for the Ukrainian Greek Catholic underground Church is evident. His contribution was both moral and structural. It is through his enthusiasm, courage and leadership that the faithful continued to secretly and devotedly practice their faith in the midst of adverse and perilous circumstances. He formed the religious sisters through his recruitment and teachings. He organized them into small house communities. They, in turn, became the catechists who formed the laity in the church. He educated new candidates for the priesthood and ensured their ordinations. He received the “apostate” priests back into the Church, thus increasing the number of clergy who could secretly, if not overtly, serve the people. Most importantly, he did not refuse to be consecrated a bishop in a Moscow Hotel room, and thus he ensured the continuance and survival of the underground Church. As a bishop, he ordained many priests and more significantly he consecrated other bishops, in particular, Bishop Volodymyr Sterniuk. His choice of Bishop Volodymyr was very providential. Bishop Volodymyr was able to continue his work as a bishop clandestinely until the late 1980’s without being arrested. He, along with others, became instrumental in gaining the legalization of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in 1990.

Blessed Vasyl was a great man and influenced the future of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. Sr. Modesta said this beautifully in her interview: “I saw before me a person of great intelligence, culture, profound faith, and a selfless sacrificial laborer for the salvation of human souls. In our conversations, I sensed a great wisdom and goodness. He lived in this way and he encouraged others – priests and us sisters, to reach for these same virtues. … I experienced his fatherly protection and sincere love, filled with self-sacrifice for the service of God’s people. Now, I understand that, if Father Vasyl Velychkvosky … had not gone to Moscow to meet his Beatitude Josyf, there would not have been an underground church. There would have been no monasteries and I would not have been a nun. …. God gave me three years to reap from Bishop Vasyl’s spiritual conferences, but I still breathe their contents today.”[66] Bishop Vasyl’s influence over the spirit and the courage of the underground church is still evident in the life of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church of today.

Reference Sources

BVV, Blessed Vasyl Veleychkovsky Shrine & Museum Archives. 250 Jefferson Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Bachtalowsky, C.SS.R. Stephen. 1991. Vasyl’ Vsevold Velychkovsky Redemptorist Bishop-Confessor of the Faith. Yorkton, SK, Canada: Redeemer’s Voice Press.

- До Світла Воскресіння крізь терни катакомб – Підпільна діяльність та легвлізація Української Греко-Католи цької Церкви. Lviv, Ukraine: Institute of Church History Ukrainian Catholic University.

[1] Pope John Paul II visited Ukraine June 23-27, 2001. On this occasion he had four beatifications for the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church: Blessed Josaphata Hordashevska; Blessed Priest Martyr Emilian Kovch; Blessed Bishop & Martyr Theodore Romzha; and Blessed Nicholas Charnetsky and 24 Companion Martyrs. Blessed Vasyl Velychkovsky was among the Companion Martyrs.

[2] Blessed Vasyl Veleychkovsky Shrine & Museum Archives, Font 2, Section III, Subsection C, Tape 12 (BVV, f.2, III, C, tape 12) – interview with Bishop Julian Voronowsky, 2005

[3] Father Nicholas Charnetsky, a Redemptorist, was sent by Metropolitan Andrey Shyptytsky to worked with the new immigrants from Halychyna and with the Orthodox faithful who were petitioning the Metropolitan for spiritual help. Charnetsky was consecrated a bishop in 1931. He was arrested April 11, 1946, imprisoned for 11 years and died April 2, 1959. On June 27, 2001, he was beatified as a martyr by Pope John Paul II.

[4] Bachtalowsky, C.SS.R. Stephen. 1991. Vasyl’ Vsevold Velychkovsky Redemptorist Bishop-Confessor of the Faith. Yorkton, SK, Canada: Redeemer’s Voice Press. pg. 83

[5] BVV, f.2, I, A, vol. 1, pg. 312 – from the KGB documents concerning the 1st Arrest

[6] BVV, f.2, I, A, vol 1, pg. 221-222 – from the KGB documents concerning the 1st Arrest

[7] Ibid. vol. 1, pg. 223

[8] Bachtalowsky, Stephen. 1991. pg. 86

[9] BVV, f.2, III, B, tape 3 – interview with Sr. Innocentia Sytko, 2004

[10] BVV, f.2, III, B, tape 9 – interview with Boris Mirus, 2004

[11] Ibid

[12] ibid

[13] BVV, f.1, II, A, doc 2 – the protest letter is found in BVV

[14] BVV, f.2, III, C, tape 12 – interview with Bishop Julian Voronowsky, 2005

[15] BVV, f.2, III, B, tape 7 – interview with Sr. Modesta Senyk, 2004

[16] Sister Monica, was instrumental in Blessed Vasyl’s vocation, introducing him to the Redemptorist Congregation. She was also arrested by the Soviets in 1949 and died in prison in 1951.

[17] BVV, f.2, III, B, tape 1 – interview with Sr. Serafyma Salo, 2004

[18] BVV, f.2, III, B, tape 3 – interview with Sr. Innocentia, 2004

[19] BVV, f.2, III, C, tape 5 – interview with Sr. Iryna Korduba ,2005

[20] BVV, f.2, III, B, tape 4 – interview with Sr. Claudia Velhosh, 2004

[21] BVV, f.2, III, C, tape 5 – interview with Sr. Iryna Korduba, 2005

[22] BVV, f.2, III, C, tape 12 – interview with Bishop Julian Voronowsky, 2005

[23] When Bishop Charnetsky was released from the hospital in late March 1959, he was taken to Fr. Vasyl’s apartment. It was there that he died on April 2, 1959. His body was then secretly transferred to his own home on Vechernia Street. Only there was his death announced, so as not to draw attention to the fact that Fr. Vasyl’s apartment was already a center of church activity.

[24] An antimension is a cloth with the image of the burial of Jesus upon it. Into it is sewn a holy relic. Upon this cloth, which is blessed by the bishop, the priests celebrate the Divine Liturgy.

[25] BVV, f.1, III, D, doc 1 – a prayer of absolution for Apsotate priests, handwritten by Bishop Velychkovsky

[26] BVV, f.2, III, C, tape 12 – interview with Bishop Julian Voronowsky, 2005

[27] Bishop Ivan Sleziuk was secretly consecrated a bishop in 1945 by Bishop Hryhorij Khomyshyn of Ivano Frankivsk. He led the Eparchy of Ivano Frankivsk from 1957 to 1973 until he died a martyr’s death. He was beatified with Blessed Vasyl on June 27, 2001.

[28] Bachtalowsky, Stephen. 1991. pg. 137 – sermon by Bishop Volodymyr Malanchuk, C.Ss.R.

[29] BVV, f.2, V, A, doc 3 – letter written by Metropolitan Josyf on January 27, 1963

[30] BVV, f.2, III, B, tape 10 – interview with Sister Mykolaya Pandrak, 2004

[31] BVV, f.2, III, B, tape 13 – interview with Bishop Michael Hrynchyshyn, C.Ss.R., 2004

[32] BVV, f.2, III, B, tape 10 – interview with Fr. Ivan Dankiw, 2004

[33] Fr. Myhaylo Vynytsky, C.SsR., a Redemptorist priest, was very active in the underground Church. He was arrested and imprisoned four times, but would not discontinue his pastoral work. He died after the Church was freed in 1996.

[34] BVV, f.2, III, C, tape 12 – interview with Bishop Julian Voronowsky, 2005

[35] There was a close connection between the Lithuanian church and the underground Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. There were monthly trips between the two. The Lithuanians were able to print catechisms which were then smuggled into Ukraine. They also provided the printing of antimensions for use in the Divine Liturgy.

[36] BVV, f.2, III, B, tape 3 – interview with Sr. Muza Solomon, 2004

[37] ibid

[38] Bishop Ivan Sleziuk, consecrated secretly by Bishop Hryhorij Khomyshyn of Ivano Frankivskin 1945, was imprisoned in 1962. Upon his release in 1967, he consecrated a Basilian, Father Sofron Demeterko in 1968 to the episcopacy. Bishop Demeterko served the church in Ivano Frankivsk, while Bishop Sterniuk served the Church in Lviv and Ternopil. Bishop Alexander Khira, ordained secretly by Bishop Teodor Romdza of Zacarpathia in 1945, was in exile in Karaganda. While there, he consecrated Father Josaphat Fedoryk to the episcopacy in 1964, who himself lived in Kyrgyzstan. In time he returned to Ukraine.

[39] BVV, f.2, III, E, tape 5 – interview with Sr. Onufria Maik, 2008

[40] BVV, f.2, III, B, tape 8 – interview with Vasyl Manko, 2004

[41] Bachtalowsky, S, 1991. Pg 46-94. This autobiography covers his life from birth until 1956.

[42] Metropolitan Josyf Slipyj was name Major Archbispoh in 1963 and Cardinal in 1965.

[43] BVV, f.2, V, B, doc 20 – a testimonial of Episcopal consecration document, Zagreb May 3, 1967

[44] BVV, f.2, III, C, tape 12 – interview with Bishop Julian Voronowsky, 2005

[45] BVV, f.1, I, A, doc 21 – letter of Velychkovsky to Redemptorist Superior General, May 3, 1967

[46] BVV, f.2, V, B, doc 21 – letter of Metropolitan Maxim Hermaniuk to the Cardinal Samore, July 19,1967

[47] BVV, f.2, V, A, doc 4 – letter of the Protoarchmandrite A. Velykyj to Velychkovsky, May 3, 1967

[48] BVV, f.2, V, A, doc 5 – letter of Major Archbishop Josyf Slipyj to Velychkovsky circa May 1967

[49] BVV, f.2, V, A, doc 6 This was written on a cloth which was then sewn into the garment to make it easier to smuggle across the Soviet border. This letter was smuggled to Bishop Vasyl through his nephew’s wife, who brought it from Zagreb to Lviv.

[50] These two documents, together with the letter from the Basilian ProtoArchmandrite, later were hidden in a jar in a garden of the Basilian Sisters in Lviv. They were unearthed in 2004 and are now part of the Blessed Vasyl Velychkovsky Shrine and Museum Archives.

[51] BVV, f.2, III, D, tape 4 – interview with Orest Vynytsky, 2007

[52] BVV, f.1, III, B, doc 1 – This book was found in a museum in Lviv for atheism as an example of anti-soviet propaganda. The original is found in Blessed Vasyl Velychkovsky Shrine and Museum Archives. It is now published in both Ukrainian and English.

[53] 2012. До Світла Воскресіння крізь терни катакомб – Підпільна діяльність та легвлізація Української Греко-Католи цької Церкви. Lviv, Ukraine: Institute of Church History Ukrainian Catholic University. pg. 18

[54] Bachtalowsky, S. 1991. pg. 16

[55] Fr. Bohdan Smuk was taught theology personally by Bishop Vasyl in preparation for ordination to the priesthood. Bishop Vasyl taught him for three years, 1966-1969.

[56] BVV, f.2, III, I, tape 1 – interview with Fr. Bohdan Smuk done by his son and obtained by the Archives in 2012.

[57] BVV, f.2, III, B, tape 3 – interview with Sr. Muza Solomon, 2004

[58] BVV, f. 2, III, G, tape 4 – interview with Ihor Rak who was the child interrogated, 2010

[59] BVV, f.2, III, B, tape 3 – interview with Sr. Innocentia Sytko, 2004

[60] BVV, f.2, II, E, pg. 302 – taken from the judicial commission denial of Velychkovsky’s complaint letter

[61] BVV, f.1, II, B, doc 6 – Velychkovsky’s complaint letter written on October 2, 1969

[62] BVV, f.2, II, E, pg. 301 – KGB documents of Velychkovsky’s second arrest

[63] BVV, f.2, III, C, tape 21 – interview with Sr. Justyna Tverdohlib, 2005

[64] BVV, f.2, X, A – Documents prepared for the Vatican in the Process of Beatification. Il Servo di Dio Vasyl Velyckovskyj 1903-1973. Document 49 – testimony of Bishop Michael Wiwchar. A copy of the Process is in Blessed Vasyl Velychkovsky Shrine and Museum Archives

[65] BVV, f.2, III, B, tape 14 – interview with Maria Matwychuk, 2004

[66] BVV, f.2, IV, A, doc 20 – testimony of Sr. Modestsa Senyk